Part 1: Dream Presentation

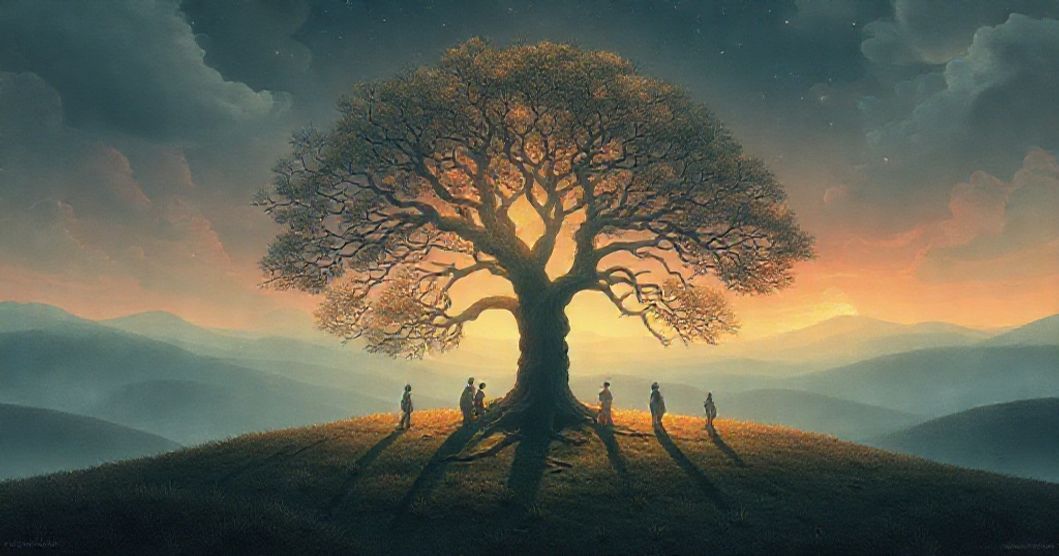

Dreams often manifest our deepest emotional landscapes, and this narrative reveals a complex interplay between family bonds, responsibility, and the unconscious processing of life's burdens. The dream begins with an ancient oak tree—a powerful symbol of rootedness, growth, and generational legacy—emitting three baby versions of the dreamer’s six-year-old brother. This surreal imagery immediately signals the dream’s focus on duplication, identity, and vulnerability. The dreamer’s tears and fear of parental judgment (“I knew my mom would be mad”) establish a core conflict: the desire to protect or recreate something precious (the brother’s childhood self) versus the fear of violating family norms. The physical struggle with the “heavy” baby clones—dropping one on “wet grass” and the visceral weight of the swaddled figures—translates the emotional burden of caregiving into a tangible, almost painful reality.

The neighbor’s unexpected assistance introduces a paradox: the dance-like movement in his yard contrasts with the dreamer’s gravity, suggesting a need for lightness in the face of overwhelming responsibility. The three car seats, arranged with practicality, symbolize structure and protection, yet the dreamer’s cramped position between the console and backseat hints at the precariousness of balancing caregiving with personal space. The journey forward in the car, though cut short, suggests an attempt to resolve or escape the conflict—an escape that mirrors the dreamer’s waking desire to “go back to my dorm to clean up after my roommate,” a cycle of caregiving that feels inescapable.

The rewritten dream narrative preserves these core elements while deepening emotional resonance: the tree’s roots as a source of “unexpected life,” the wet grass as a physical manifestation of emotional dampness, and the neighbor’s cheerful dance as a jarring reminder of life’s incongruous rhythms. The waking context—illness, cleaning burdens, and generational conflict—provides critical emotional anchor points, framing the dream as a psychological response to feeling overwhelmed by responsibilities.

Want a More Personalized Interpretation?

Get your own AI-powered dream analysis tailored specifically to your dream

🔮Try Dream Analysis FreePart 2: Clinical Analysis

Symbolic Landscape: Archetypes and Imagery

The tree stands as the dream’s central symbol—a Jungian “world tree” bridging the conscious and unconscious, its roots (and the clones they birth) representing the dreamer’s connection to family history. The baby clones are not literal duplicates but symbolic of the dreamer’s internalized version of their brother’s childhood self, a representation of vulnerability and innocence they may feel compelled to protect. The “wet grass” evokes emotional dampness or unresolved conflict, while the act of “hiding” the clones reflects the dreamer’s unconscious avoidance of confronting family expectations directly. The car seats, a mundane object, transform into a symbol of structured responsibility—both the dreamer’s desire to “fix” or “protect” the clones and the burden of caregiving roles they feel forced into.

The neighbor’s dancing introduces a paradoxical element: his lighthearted movement in a crisis suggests the dreamer’s need for flexibility in the face of rigidity. In dreamwork, dancing often symbolizes release, joy, or the ability to adapt—here, it hints at the possibility of lightening the burden of caregiving through community or unexpected support.

Psychological Undercurrents: Jungian and Freudian Perspectives

From a Jungian lens, the clones represent the dreamer’s “shadow” aspect of sibling identity—the parts of themselves they may have repressed or idealized. The six-year-old brother, a younger self or a “shadow” child self, becomes duplicated to explore themes of legacy, family patterns, and the fear of losing one’s core identity. The tree as a source of birth/growth aligns with Jung’s concept of the “anima/animus” archetype, where the tree embodies the dreamer’s connection to ancestral or family “roots.”

Freud’s perspective might interpret the clones as a manifestation of the dreamer’s unconscious guilt over avoiding family responsibilities (cleaning, caregiving) while feeling burdened by them. The “mother’s anger” could symbolize the superego’s judgment, while the “hiding” represents repressed feelings of inadequacy in meeting familial expectations. The physical struggle with the heavy babies mirrors the dreamer’s waking struggle with illness and exhaustion, with the body itself becoming a site of conflict between caregiving and self-preservation.

Cognitive dream theory adds another layer: the dream processes stressors (illness, cleaning, roommate dynamics) through symbolic imagery. The “clones” may represent the dreamer’s inability to “unplug” from caregiving, even in sleep—their mind replays the cycle of responsibility, turning it into a surreal, almost comical scenario (babies, car seats, dancing neighbor) to make sense of overwhelming patterns.

Emotional and Life Context: Unpacking the Layers

The dreamer’s waking context—sickness, cleaning fatigue, and generational conflict—illuminates the dream’s emotional triggers. The two-day illness likely amplified feelings of vulnerability, making the “baby clones” (representing childhood innocence or helplessness) feel both precious and burdensome. The kitchen mess, a symbol of unmet expectations (grandma’s promise to clean, broken), becomes a microcosm of the dreamer’s broader experience: they are caught in a cycle of caregiving without reciprocity, both at home and in their dorm.

The age gap between the dreamer (18) and brother (6) is psychologically significant. The older sibling role often carries implicit responsibilities, and the “clones” may represent the dreamer’s internalized pressure to “protect” or “recreate” the younger self’s carefree state—an impossible task that becomes the dream’s central conflict. The “wet grass” and “dropped clone” reflect the dreamer’s fear of failing in this caregiving role, a fear that materializes as physical clumsiness in the dream.

Therapeutic Insights: Unpacking the Symbolic Load

This dream invites the dreamer to explore three key areas: setting boundaries in caregiving relationships, honoring their own needs, and integrating childhood identity with adult responsibilities. Journaling exercises could help clarify the specific “clones” in question—are they literal siblings, childhood selves, or unmet emotional needs? Reflecting on the tree’s role as a source of “new life” might reveal that the dreamer’s unconscious is seeking healthier ways to nurture relationships rather than burdening themselves with care.

The neighbor’s unexpected assistance suggests practical steps: reaching out to trusted individuals (friends, family) for support rather than shouldering the burden alone. The car seats symbolize structured support systems; perhaps the dreamer needs to create clearer boundaries around their time and energy, even if that means saying “no” to some caregiving requests.

FAQ Section

Q: What does the tree symbolize in the dream?

A: The tree represents family roots, generational legacy, and the unconscious “birth” of new emotional patterns. Its roots embody the dreamer’s connection to ancestral or childhood self, while the “clones” reflect a desire to preserve or recreate aspects of that identity.

Q: Why did the dreamer feel so burdened by the baby clones?

A: The weight and difficulty of caring for the clones mirror the dreamer’s waking experience of unreciprocated labor—cleaning, illness recovery, and dorm responsibilities. The dream literalizes this burden, making the invisible feel tangible.

Q: How does the neighbor’s dancing relate to waking life?

A: The neighbor’s unexpected support symbolizes the possibility of community or unexpected help in caregiving situations. It suggests the dreamer might benefit from reaching out to others rather than facing challenges alone, a shift from isolation to collaboration.